|

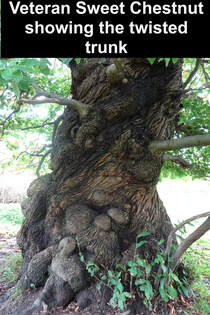

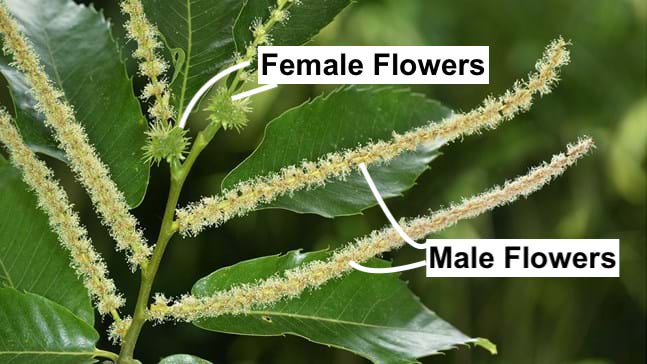

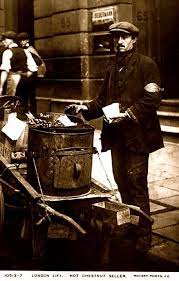

The Sweet Chestnut, thought to be introduced to England by the Romans from its native home in the Mediterranean, can live to 700 years and reach a height of 35 metres. After about 25 years it starts to produce the distinctive prickly burrs which contain the edible Chestnut. Most of our Chestnuts are imported but going chestnutting in October is a great foraging activity. Young trees have a smooth, grey bark while on veterans it becomes deeply fissured and twisted.

0 Comments

The Elder can grow to a height of 15 metres and live up to 60 years. The bark is greybrown and deeply ridged. Elder grows particularly well where nitrogen levels in the soil are high from the presence of organic matter - farmyards, churchyards, badger sets and rabbit warrens for example.

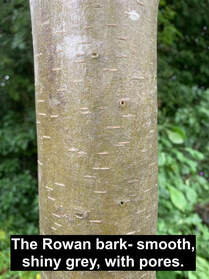

The Rowan Tree is a quick-growing, widespread tree of the Sorbus family, that can survive in many different conditions including wasteland, scree, and on cliffs. Its common name - Mountain Ash - derives from its ability to grow up to 1,000 metres above sea level, even surviving in crevices and cracks in rocks.

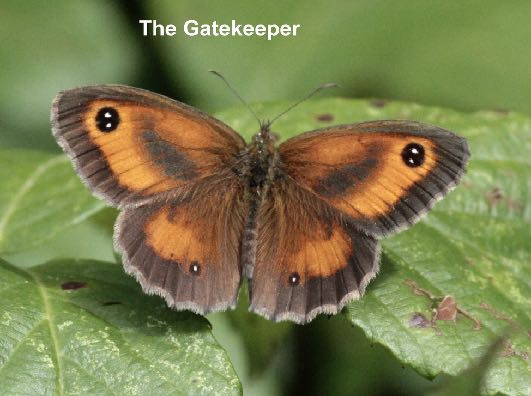

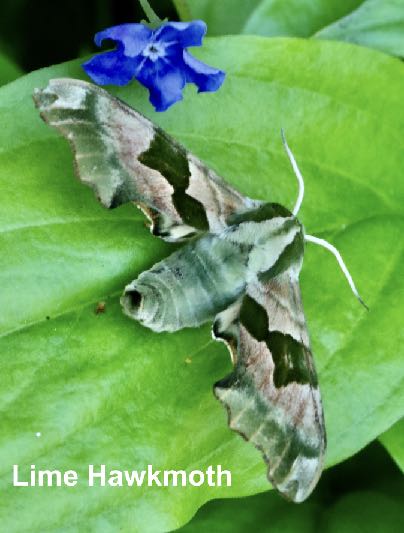

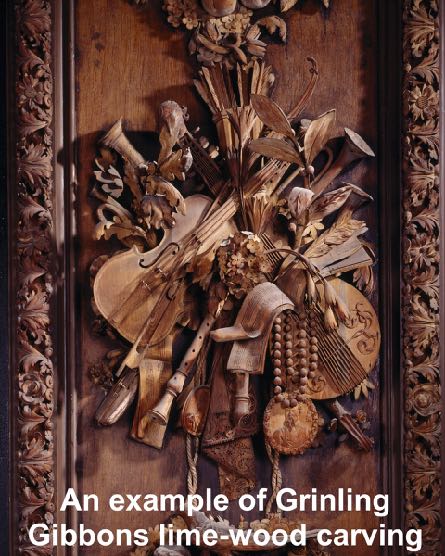

13/7/2023 0 Comments Insects on the MeadowSome insects (and spiders) you can see on the new meadows by the viewpoint and around the Parkwood Springs site in the summer. The Lime (or Linden) Tree is a fast growing tree that can reach 40 metres in height. There are several species found in Britain, but the most commonly planted is the Common Lime, a natural hybrid between the small and largeleaved Lime. The Common Lime is tolerant of many different growing conditions which has led to it being planted widely in parks, churchyards, country estates and along urban streets. Many Sheffield roads, including several local to Parkwood Springs, are lined with Lime trees. The bark is ridged and mature trees will typically have many shoots and burrs near the base of their trunks. The Lime is an elegant tree, even in winter, with its downward-sweeping branches.

18/6/2023 1 Comment An update from our 2023 May AGMWe moved our Groups AGM back to May time this year. In doing so, we want to update on all that has happened since November 2022, in addition to providing a space to illustrate our ongoing events and activities on Parkwood Springs. Firstly, a range of activities and events have continued to be held on site, primarily our Forest Garden and Conservation sessions (look at our new steps!) and guided walks. The Dawn Chorus, fungi and wildflower walks continue to be very popular indeed! In October last year we were able to hold another spectacular Lantern Procession once more. AGM update On the 9th May, our AGM focused on three major areas of discussion: the development of the Places to Ride project, the restoration of the closed Landfill site and the potential redevelopment of the old Ski Village site. We will explain those three areas outlined above in more detail and how we approached the challenges and benefits linked to the redevelopment of the site. As you can see from the above photo, work on the new paths and cycle paths has started to take shape on Parkwood Springs. There will be more work to make the paths easier to walk on in the autumn. In a past update we discussed the four packages of work as part of the Places to Ride scheme. Later on in the summer the next work package, the provision of toilets, a kiosk and storage units will begin construction. The Council is also beginning the process of appointing an operator for the kiosk. As a result we expect some potential challenges around accessing parts of the main car park off Shirecliffe Road, but we will keep you updated on progress. Landfill Restoration As we all know, the Landfill has been closed for some years now. The restoration is moving forward, and we know that before long we’ll have access to a growing network of paths across it. But it’s moving forward quite slowly. It hasn’t been helped by the change in ownership from Viridor to a new company, Valencia. There have been issues about drainage with Yorkshire Water, and legal issues to do with land ownership, but we gather these are now being sorted out. The good news is that everyone is committed to the public having access to that network of paths. Valencia want to make sure that people are safe using the site, and obviously we do too. Therefore there will be restrictions for some while yet. However we understand that Valencia are now trying to speed things up, and we hope that this will mean we can go to at least some new areas by the autumn. The outstanding issue for us is about our wish to see a wetland area on the closed Landfill, for nature, biodiversity, and to be an attractive feature for people. We have been pressing for this for years. We thought that we had agreement from Viridor (the previous owners) and were pleased to see it in documents submitted to the Council for planning permission. When permission was granted, the wetland area was reflected in the planning conditions attached to it. However, what was dug out was a rectangular ‘tank’, with steep sides on three of the four sides (steep sides really limit its value for wildlife). The area can be glimpsed through the trees from the ‘Beacons’ Viewpoint (where the poles are). We realised that what Valencia dug out meets the need to manage the drainage of surface water, but it was a long way away from what we wanted, and thought had been agreed. The committee has spent a lot of time pressing for improvement. Council officers have taken our comments and representations seriously, and we understand that there are on-going discussions with Valencia. It looks as though there will be some improvements achieved through planting of vegetation and some softening of the edges. However we fear that it will not be as good an outcome as if Valencia had taken the issue seriously earlier. Ski Village redevelopment and Transport Options Study

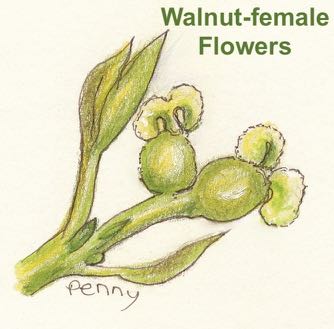

The Council are continuing to try to bring in investment to redevelop the old ski village area, which they have called the ‘Opportunity Site’. The main obstacle to development is transport access, which is currently only available through the narrow bridge on Douglas Road. The Council’s consultants Mott MacDonald began a transport assessment last year which is looking at all aspects of access to the site, highways, public transport, walking and cycling. The output from this assessment will be a critical part of any future submission for funding from government. The Friends group and other local groups have participated in the assessment, and we are continuing to monitor what is happening. The first phase of the study has been completed and we are waiting to see the report which will show what has been done, and what will be happening next. We understand that three highway options will be investigated with detailed costings and modelling of the effects on the wider transport network. These will be brought together with the public transport, walking and cycling options. We will be looking in detail at the first phase report, and have urged the Council to continue involving other local stakeholders such as the Friends of Wardsend Cemetery, KINCA and the Upper Don Trail Trust. Our young Walnut Tree in full leaf at the Forest Garden, Parkwood Springs

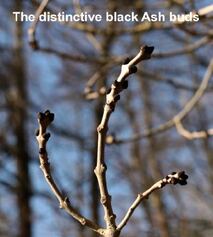

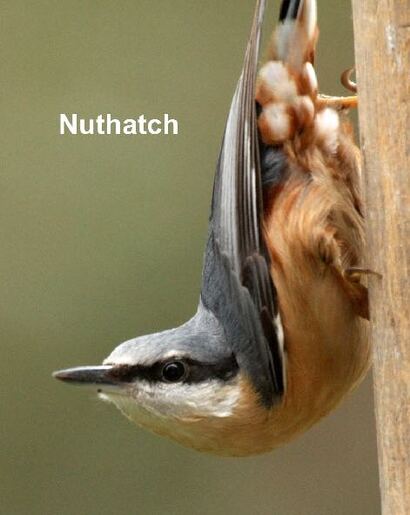

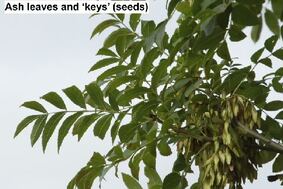

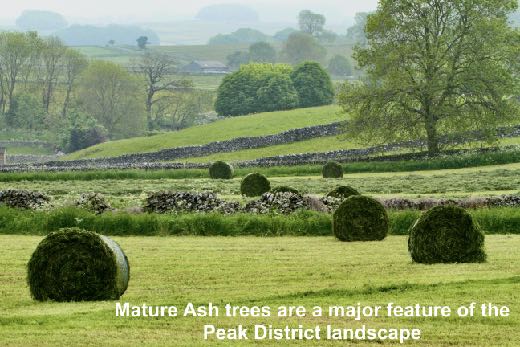

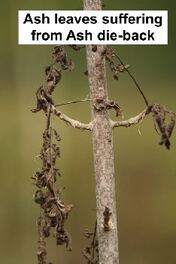

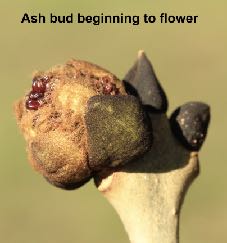

Ash is a fast-growing, native tree, quick to colonise woodland and openground. Ash is the UK’s third most common species after Oak and Birch and makes up 13% of our broadleaved woodlands. In some areas Ash is the dominant tree species. The flexible wood has many uses, and, though no species is dependent on Ash, many birds and insects benefit from it. Sadly an estimated 6 out of 7 Ash trees could succumb to the devastating disease of Ash die-back.

Each month we will be featuring a species of tree found on Parkwood Springs. Visit our tree of the month page for further details here. This month we will be highlighting Blackthorn (Sloe). The Blackthorn grows to a height of 6-7 metres and can live for 100 years. It has a dense growth and naturally suckers to produce thickets which, together with its long, strong thorns, make it a safe nesting and roosting site for many small birds and mammals, including the nationally threatened Nightingale and Turtle Dove. The same properties make it a valuable hedging plant.

|

|

About us |

Resources |

|