|

The Beech, the third most common tree of British woodlands, grows to over 40 metres and can live well over 300 years, or up to 500 years if pollarded. It is truly native in South East England and South Wales, colonising as the ice retreated after the last ice age. It has naturalised and been planted elsewhere in the UK. Mature beech woods can form a cathedral-like high-arched canopy. Beech are shallow-rooted and many old trees were lost during the hurricane of 1987. Some Parkwood Springs Beeches are multistemmed and may be survivors of older trees which were cut for firewood by impoverished local people during the 1930’s Depression. Beech is a favourite decorative hedge having beautiful foliage and leaves that linger on well into winter. These act as shelter for birds and small mammals.

0 Comments

The Horse Chestnut was introduced to England in the 16th century from Türkiye and became very popular for avenues and specimen trees in Stately Homes and urban parks from the 17th century. It was especially valued for its decorative flowers, commonly known as ‘candles’. The fruits have long been popular with children playing the game ‘conkers’. There are nearly half a million in Great Britain and Capability Brown planted 4,800 on just one estate in Wiltshire. Horse Chestnut trees can grow to a height of 40 metres and live for 300 years. The tree grows rapidly and in a range of soils. There is a decorative pink flowered cultivar often grown in parks.

Apple trees are not native to Britain. Domestication of Apples probably started around 10,000 years ago and they are now grown world-wide, with many thousands of varieties. DNA analysis shows the earliest form of Apple is native to the mountains of Kazakhstan where it is still flourishing. No Apple variety comes true from seed. All cooking, eating and cider Apples have been developed from selective cross-breeding over thousands of years. The only reliable propagation of any variety is from clone-grafting.

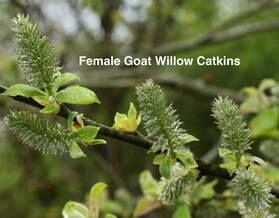

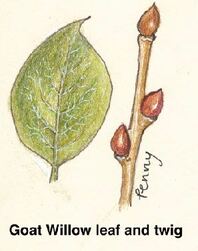

The Goat Willow is more commonly known as the Pussy Willow because of the furry, silver-grey male catkins that appear (before the leaves) in late February and March. It is one of several species of willow native to the UK. There are over 300 species of Willow worldwide but many hybridise with each other so it isn’t always easy to tell one willow species from another. Because it tolerates dry, poor soils as well as damper conditions the Goat Willow is the Willow that appears in several parts of Parkwood Springs. Goat Willow, growing up to 10 metres, can live for 300 years. It is a ‘pioneer species’ and can be found in open ground, woodland scrub and along water-courses.

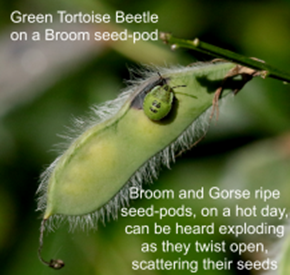

Gorse and Broom are both members of the pea family. These bushes can survive and spread quickly on poor soils aided, as with all members of the pea family, by their ability to fix nitrogen in the soil. Growing 2-3 metres high and forming dense thickets if left, they are important parts of a mosaic of different ecosystems but, if not managed, can spread to invade other valuable habitats. On Parkwood Springs we have an important inner city heathland, mixed stands of woodland, meadow and grassland. To maintain a balance we control the spread of Gorse and Broom through our conservation sessions. Volunteers are always welcome to join us doing this or other conservation work.

On 16th October 2023, Louise Bull and I heard an interesting talk by Ian Rotherham (Emeritus Professor at Sheffield Hallam University) about mediaeval deer parks in Sheffield – particularly Graves Park. It prompted me to look more closely into Parkwood Springs, which was a deer park in mediaeval times.

Why were deer parks established? Early days John Fletcher (Landscape Archaeology and Ecology, September 2007), a vet working in a Scottish deer park, has written about the ways in which early humans throughout Europe and Asia hunted deer in groups, setting a cultural tradition which seemed to have lasted for centuries. Deer roamed wild over wide geographical areas. They were relatively difficult to hunt to provide sufficient food to feed a tribe, therefore, probably since prehistoric times, communities would come together to herd deer by encircling them over a wide area and driving the animals into an enclosure. It has been recorded that archers on horseback, to demonstrate their prowess with a bow, would ride through enclosed deer herds often engaging in a frenzy of mass slaughter. Apart from effecting a cull of the larger animals and providing food to feed a tribe through the winter, such a collaborative event probably also served to promote community coherence - people hunting and feasting together. There may also have been a ceremonial function. Such an event would have celebrated the power and status of the leader of the tribe and the strength and accomplishment of participating individuals. Archaeologists in Orkney have discovered the remains of large numbers of an ancient breed of cattle which they consider were all slaughtered at the same time and must have provided meat far in excess of the needs of the local population. The animal bones were found close to a religious site of considerable proportions, which suggests that Neolithic people from far and wide must have travelled to events or ceremonies where large numbers of animals were slaughtered. Anglo Saxon Britain Fletcher describes how in Anglo-Saxon times; deer were driven by beaters and dogs into areas enclosed by thickets or hedges of impenetrable shrubs such as holly – known as hags or holly hags (haiaes). Following the ancient cultural tradition, the deer would be shot (with bows and arrows) and the meat hung for food for the Lord of the Manor’s table or to be given as gifts to ensure the allegiance of local nobility or the clergy. Venison was a high status meat – the preserve of the wealthy. There were strict laws to protect deer from poachers. People who could keep deer on their land were able to use the activity of hunting, and the venison produced, both as a status symbol and as a means of maintaining power in their community. Roe deer, which were indigenous to Britain (and most common in Yorkshire), were smaller than red or fallow deer, did not roam in larger herds, therefore were harder to corral. They mainly fed by browsing in woodland rather than grazing open grassland, so were less in evidence. They were still able to be herded by beaters and killed by skilled hunters. Herding the deer provided a much easier target for the hunters. Some used canvas fencing to channel the deer into the hags as deer would run along clear pathways. In Scotland deer would follow streams or rivers when frightened, therefore they could be channelled through river valleys. The Normans in Britain After the Norman Conquest large estates were gifted by King William 1 to Norman noblemen who had fought with him. One such estate was the Cowley Estate in Chapeltown, which must have already been established as an estate in Anglo Saxon times. It was gifted to a Norman family, the de Louvetots, who in turn gifted the estate to relatives, the De Mounteney family. The De Mounteneys lived at Cowley Hall, Chapeltown – ‘a large castellated manor house’ (Hunter’s Hallamshire). Shirecliffe - and Parkwood Springs as we know it today – was a sub-manor of the Cowley Estate. From the 12th century landowners could be granted the ‘right to free warren’ : ‘Hunting certain animals: pheasant, partridge, hare, rabbit, badger, polecat and pinemarten within a prescribed area. This was often the forerunner to the fencing of demesne land to create a deer park. … more than 80 grants of free warren were given in South Yorkshire and in nearly a third of these a deer park was subsequently created.’ (Mel Jones). Some wealthy families had already begun to enclose areas for deer to graze. Norman landowners wishing to prevent their deer from escaping onto neighbours’ properties, began to enclose, in some cases, vast areas of their parkland. They dug ditches and fenced with palings woodland and open farmland to create ‘parks’ which were characteristically grass meadows dotted with ancient trees and areas of woodland. Because of the difficulty of ditching and fencing corners, the shape of parks was typically rectangular with rounded corners. Herding deer into enclosed areas was the prerogative of the wealthy and demonstrated their power and status within their community. The Normans continued to enforce strict laws governing access to land and hunting rights. Villagers were fined heavily – or worse – if found to have hunted - all but badgers - on land owned by the gentry. (Badger meat didn’t taste good.) Wild deer were deemed to be the property of the King and landed estates within a short distance of a Royal Forest needed a licence to enclose land - without the right to entice the King’s deer onto it (Mel Jones 1996). Families who had already established a deer park were able to retain their park without a licence from the king, therefore deer parks were becoming popular prior to Norman times. Royal forests at Conisbrough, Sherwood and later, Kimberworth Park, were close, therefore landowners in the Sheffield area were required to apply for a licence. Mediaeval Shirecliffe Deer parks were often established at a distance from the manor house of an estate and in 1392, towards the later years for applications for license to create a deer park, Sir Thomas de Mounteney was granted a licence to create a deer park at Shirecliffe, which was at a distance from the family’s main residence of Cowley Hall. According to Hunter’s Hallamshire: ‘Sir John Mounteney had a license from the Crown to inclose 200 acres of land, 300 acres of wood and 20 acres of his demesne land in Shirecliffe and to make a park of the same.’ They had ‘great woods and abundance of redd deare, and a stately castle-like house moated about.’ (Dodsworth). The stately house would have been Cowley Hall, Chapeltown. By the 15th century most country houses in the Sheffield area had enclosed a deer park. Sheffield Park, home to the Earls of Shrewsbury, stretched from Sheffield Castle to the east of the town centre with a circumference of 8 miles. Sheffield manor was situated on part of the land enclosed by the park, which was the largest in the area covering 2,462 acres (Mel Jones). Clearly the Shirecliffe estate already had red deer on their land. The indigenous roe deer, however, were less profitable than the larger breeds, therefore by the 12th century the Normans had brought fallow deer to Britain - and red deer were more commonly brought onto estates. The Normans had introduced rabbits to their wealthy estates as an additional food source. Cattle, sheep, pigs, game birds and other animals were frequently also kept in deer parks, which were not primarily created for hunting although hunting did take place in the larger parks. Most were deer farms to provide food for the table (Mel Jones). Wharncliffe ‘Chase’ for example would have been a park where hunting took place. At such a distance from Cowley Hall it is likely that the de Mounteneys would have needed a park keeper on site to maintain and guard the park. The old Shirecliffe Hall which would have stood approximately across the junction of Cooks Wood Road and Shirecliffe Lane may have originally been built for a park manager. It was also said to have been a hunting lodge, possibly with a tower to view both deer and the Don valley into Sheffield and beyond. This suggests that the family at Cowley may have entertained guests and hunting parties at Shirecliffe Hall, although it is not clear whether hunting took place here. As was typical of deer parks, the shape of Parkwood Springs is more or less rectangular -with rounded corners at Scraith wood in the north and following a curve in the river Don to the south. The original park must have been larger than Parkwood Springs today, as the area from 1637 to the present day is about 300 acres compared with 520 acres enclosed by licence in 1392 in the reign of Richard II. A bank and ditch close to the car park at Shirecliffe Road might be part of an enclosure fence, perhaps to keep the deer from the hall. Boundary fences were originally intended to keep deer in and intruders out, but as deer parks developed and evolved over the years, they were also used to divide sections of the woodland. The large trees became valuable for their timber, sticks for kindling and dead wood was used to keep fires in the Hall burning for heat and cooking. Coppicing produced wood suitable for fence posts and tool handles etc. Coppicing meant cutting trees to the ground. The new shoots from the base of the coppiced tree would be left for 10 years to grow tall, straight new trunks before being cropped again. By coppicing areas of woodland in rotation, a constant supply of wood could be achieved. Young shoots and the foliage of the older trees would be browsed by both cattle and deer. To protect the new growth and the sometimes enormous older trees from being decimated by deer, coppiced areas and older woodland would be fenced off. ‘Spring woods’ were created for coppiced woodland, giving the name to Parkwood Springs. However, not all of Parkwood Springs contained spring woods – at least in earlier times. On the map of 1637 a number of separate areas of woodland were demarcated. ‘Scraith Banke, Shirtcliffe Park Wood, The Lords Wood, Oaken Banke Wood and Cooke Wood.’ To the northern end of the current site lies the pond at Oxspring bank, which may be the remains of fishing lakes which were common in other deer parks to provide fish for times when meat was not to be eaten for religious reasons. The area and boundary plan of Parkwood Springs as it appears on the map of 1637 are not dissimilar from the area of Parkwood Springs seen today. In winter the deer would be taken to lower grassland – a lawn, ‘laund’ or ‘lound’ – as in Chapeltown’s Loundside – to graze and be fed with cut holly and hay grown for winter fodder. Holly was grown in the ‘hags’ or ‘Hollins’. We do not know whether deer from Parkwood Springs would be taken to the ‘Lound’ at Chapeltown for over- wintering. Herding may still have taken place to move deer down to lower pastures. Ian Rotherham showed an engraving of Queen Elizabeth 1st engaged in shooting deer by standing on a raised platform in front of which deer were driven to provide a target for her – proving that by the 1600s deer hunting was still an aristocratic sport - made easier by herding. At that time, however, changes were taking place which signalled the beginning of the end for deer parks. In pre-industrial ages wealth was generated for the landowner by the use of land and by enclosing land for the sole use of wealthy families. It was commented that there was more land enclosed in mediaeval times than as a result of the 18th century enclosure acts. Livestock and woodland provided food, fuel and timber which were profitable. They maintained the high status of the landowner by demonstrating his power and wealth. Gifts of high status meat or timber to other nobles assured their allegiance and enhanced the landowner’s position with the church when gifts were given to charity or to the clergy. The De Mounteneys lived at Cowley and Shirecliffe throughout the mediaeval period as the deer park gradually changed and evolved. The last member of the family to reside there was John de Mounteney who in 1536 was assaulted in the porch of the Parish church in Sheffield (Sheffield Cathedral) and died from his injuries. The estate was sold in 1572 as ‘a very valuable acquisition’ to the 6th Earl of Shrewsbury who took it into the manor of Sheffield. Before 1616 ‘ an undated document written for the 7th Earl of Shrewsbury listed ‘Oken Bank Springe’, ‘Shercliffe Parke’ containing 80 acres of coppice and ‘Skreathe Wood.’ (Mel Jones). This document suggested a transition to greater areas of parkland becoming devoted to coppicing rather than grazing. The de Mounteney heirs contested the sale regaining the property and land but leasing it to tenant occupants. The map of 1637 shows sections at Neepsend which were leased to local people such as the Rawsons, who must have managed Rawson Spring Wood. ‘Great Ox Close’ and ‘Ox Dell’ are also marked, presumably fields for cattle. Many deer parks by that time were beginning to be divided into fields and some let as local farms. Social changes meant that wealthy landowners rarely lived in their country residences, and those who did were beginning to gain income from other sources. The fashion was to develop parks close to their country houses where the gentry could ride out for pleasure and view their estate when they visited their country mansions from their town houses. Mining ironstone and coal was providing income which meant the landowners were less dependent on agriculture. Business and financial interests – mainly investments abroad - for example trading in slavery, tobacco, tea etc were extremely lucrative, replacing the need for farming in the countryside. Iron smelting was also paving the way for monumental industrial change. Mel Jones noted that by the end of the 16th Century the land at Parkwood Springs had been formally ‘disparked’ and mainly turned into large coppiced woods, although during the 1600s deer were still present. By 1637 when John Harrison completed his survey of the Manor of Sheffield, Shirtcliffe Parke Wood (Old Park Wood) was recorded as coppiced wood covering 143 acres. The hall – ‘Shirtcliffe Hall farme’ - was tenanted by Richard Burrowes/ or Brough, a ‘gentleman’ (meaning he had a private income) at a rent of 8 Marks per year to be paid at ‘the Feast of Pentecost ‘(Whitsun) ‘and St. Martin in winter’ (November) – so in six monthly instalments. The property was described as: ‘a dwelling house, and ancient Chappell , one Barne, one Oxhouse, one Orchard and yard ‘’containing 1 a (acre), 3r (roods) 14p (perches)’. For information: A football pitch is 2 acres – 2 ½ acres or a football pitch with the surrounding green space makes up a hectare. A rood is a quarter of an acre and there are 40 perches to a rood – so a perch is 25 square metres. The land leased to Richard Burrowes was listed: ‘Ye Peare tree field (pasture) and next (to) a wood called Shirtcliffe Parke and great field north and containing11a 3r 23 p. The Pond Mead (pasture and arable) lying betweene the last piece north (Pear Tree Field) and Cooke Wood south, and next (to) Kitching greave east,and a wood called Oaken Banke west and containing 16a. 2r. 32p. A spring wood called Crooke Wood, wherein they get Punchwood for the use of the coalpits, some part thereof is above 32 years’ growth and some part newly cut downe, and every year cut as occasion serveth. This wood lyeth next unto the last piece in part and Charles Clayton in part south-east, and Oaken banke west, and containing 33a. 1r. 15 2-5p. A spring wood of 25 yeares growth called Oaken banke, lying between the last two pieces and the Lord’s wood in part west, and abutting upon Shirtcliffe Parke north, and the Lord’s lands in the use of Christopher Capper south and containing 24a. 0r. 27 3-5p. Pease field (arable) lying next the last piece west and Crooke Wood north and containing 0a. 2r. 27 3-5p.’ Presumably Charles Clayton and Christopher Capper were renting the lower parts of the original estate. In 1638 the lease expired on Shirecliffe Hall (Shirtcliffe Hall Farm). The tenancy of the Hall taken by Mr. Rowland Hancock - a former vicar of Ecclesfield Church (where the de Monteney family worshipped). He set up an independent church with a few neighbours but was banished to Penistone under the Act of Uniformity. The Act enforced the use of the 1662 Book of Common Prayer and anyone refusing to adhere to that form of church service was banished from the County. When the law was relaxed in 1672, Mr. Hancock returned to Shirecliffe and continued his church ‘on the independent model’ – presumably using the ‘ancient chappell’ on the estate. It may have been Rowland Hancock who in 1675 was granted the right to hunt deer in the park. Rowland Hancock’s daughter married a Sheffield lawyer named Joseph Banks and they remained at Shirecliffe Hall until they retired to Lincolnshire. Their grandson, Joseph Banks, was the scientist and botanist who set sail from Whitby in 1768 on the ship, the Endeavour, with Captain James Cook to survey the transit of Venus from Tahiti. They also mapped the coast of Australia and named Botany Bay where Joseph Banks collected many plant specimens. He ultimately became President of the Royal Society in London. Around 1800 detailed botanical records of Parkwood Springs were made by Jonathan Salt, a local table knife manufacturer of Wardsend (now in Weston Park Museum). We can only speculate as to whether Joseph Banks (Sr) had been interested in botany at Parkwood Springs and left information or passed his interest to his grandson. From the late 1600s there was evidence of charcoal burning in Parkwood. This may have been the ‘coalpits’ mentioned in Harrison’s survey. Wood was laid into a pit and covered with soil or turves leaving a space for lighting a fire under the wood. It had to be carefully watched to restrict the amount of air entering the pit so that the wood did not burn quickly but slowly charred. Sweet chestnut wood was often used as it did not burn easily. There are a lot of sweet chestnut trees at Parkwood Springs. Charcoal burners built their conical shaped huts close to the pits so that they could keep watch night and day. They used branches of trees built into a wigwam shape and covered with turves. In our History leaflet there is a reproduced photograph taken at Parkwood Springs in the 19th century of a charcoal burner standing beside his hut. Jason Thomson used the image in his sculpture ‘The Spirit of Parkwood’. 17th and 18th Century Parkwood Springs Whilst originally estate owners lived and worked on their estates, more landowners moved into their town houses, only visiting their country estates from time to time. Although deer grazing on the open parkland outside their stately homes gave an air of tranquil country living and prosperity, absentee landowners were keen to maximise the profitability of their land. They were less interested in the area or local communities, employing estate managers to manage the work on the estate, employ a local work force and collect rents from tenants. Deer were gradually abandoned in favour of more functional use of the land and its assets. Therefore by the 18th century, as industry began to demand timber for building, stone from quarrying and charcoal for steel making, the woodland at Parkwood Springs became more diversified to profit from use in industrial development along the Don valley. The Dukes of Norfolk, who eventually took ownership of the land, would have expected maximum returns on their investment whilst having little personal interest in the area. Land and properties owned by the Dukes of Norfolk were managed by an agent who lived at ‘The Farm’ - a grand house on the lower edge of Norfolk Park – now the site occupied by Granville College. The Dukes of Norfolk, whose stately home is Arundel Castle in Sussex, were obliged to stay at the Farm for a time annually. During the time of Henry Fitzalan Howard, 15th Duke of Norfolk and Sheffield’s first Lord Mayor, over half of the £100,000 gross income from Sheffield came from rents, mineral rights and markets. Profits to be made from areas such as Parkwood Springs benefited the wealthy landowner who was based elsewhere and were not used to maintain or improve the area locally. In many rural areas people complained of wealth being created locally whilst the landowners impoverished the countryside and its people by taking its wealth to the cities. Like other disparked deer parks some of the land at Parkwood Springs was divided into smaller areas and let to tenant farmers. By the end of the 18th Century the Lords Wood was completely divided into fields. Old Park Wood remained as managed woodland whilst Oaken Bank Wood was mined and quarried for clay for making bricks and for ganister for use as fire clay for the furnaces. Rawson Dam was recorded in 1783 as ‘the pond on a tributary of the river Don’. It had been marked on the 1637 map to the north of Scraith Wood. A water powered mill, known as Rawson’s Mill or Bark Mill, was used by the company of Rawson and Oxpring for their tanning business, which used bark stripped from oak trees to produce tannic acid for tanning leather. Rawson Spring Wood, a section at the northern end of Old Park Wood, would have produced a sustainable supply of oak trees from which bark could be taken. By stripping vertical strips of bark from a living tree the bark would repair for further use, or by stripping and felling coppiced trees, new areas of growth would also provide a constant supply. The tanning process Oak Bark: The solution used for tanning was traditionally made from oak bark. L A Clarkson has estimated that 90% of all leather was tanned with oak bark. The best bark came from the young trees of twenty years growth, cultivated in coppices. Stripping was mainly done in the spring when the sap was rising. The bark was levered off, and then stacked in the dry before being ground at a local mill. Sawyers, Carpenters and Peelers were hired to fell and remove the bark. The easiest way of peeling was to take the bark from trees that were still standing. The peelers used an iron ‘spud’, consisting of a rod about two feet long, with a handle at one end and a point shaped like the ace of spades at the other. Strips of bark were propped up to dry in the sun and the wind. Drying was usually complete in about a fortnight then carted to the tan-yard. The bark was ground into pieces, two to three inches long, and packed into sacks. Barkgrinding mills were introduced in the eighteenth century. The grindstone had a toothed rim. In their simplest form the grindstone was propelled by horse power around a circular trough. Oak bark was highly prized by tanners because of its high tannin content. Much of it was grown in the traditional iron-making districts, where it was used for manufacturing charcoal. The combination of the tannic acid of the oak bark with the gelatine of the hide slowly tanned the hide. J T Kelsey soaked his hides in oak bark solution for up to two years (The Weald Community Group). To produce supplies of wood for timber, bark for tanning and wood and bark for charcoal burning, the woodland on Parkwood Springs was increasingly coppiced to increase the yield, and areas of woodland felled for timber. The boundary fences, instead of keep deer inside the park, would then have been used to keep deer out to protect the trees. Mel Jones suggests that through the 18th Century in some areas of Old Park Wood were reduced to a few standard trees, whilst most other areas of woodland were coppiced. The Lords Wood was completely cleared and divided into fields rented as farmland. Ganister mining and some coal mining took place into the steep escarpment of Parkwood Springs. Ganister dust, moreso than coal dust, in the confined space of the mines was lethal when breathed in by miners. Life expectancy for the workers - as for steel workers - was extremely poor. The 1790 Map shows Shirecliffe Hall on Shirecliffe Lane, Little Pear Tree field, Great Pear Tree Field, Cook Wood, Oaken Bank Wood, Mire Acre Hill, Savage Spring, The Old Park and Scraith Wood – the only remaining area of ancient woodland. Field plans included Far Field. A corn mill and rolling mill on the river Don were signs that industry was using water power along the Don Valley, which required timber to build water wheels. Through the 18th Century Shirecliffe Hall was let to a succession of tenants until it came into the possession of the Watson family in 1775. The family remained at Shirecliffe for over 100 years. 19th Century In 1803 The Watson family demolished the old Shirecliffe Hall and built ‘a good modern house near the site’. It was probable that the Watsons may have held a ‘copy lease’ where the landowner retained the freehold on the land, but the tenant retained rights on the property. This was a system that began in mediaeval times and continued until the 1920s. The Watson’s would have needed planning permission from the Duke of Norfolk’s Estates, but were at liberty to build a new house, which was on the site of the car park at the Shirecliffe Road entrance to Parkwood Springs. The site of the ‘Kitchings’ or kitchen gardens for the old hall is still evident as ‘Shirecliffe Grove’ on Shirecliffe Lane. The drive to the new hall crossed the top of what is now Cooks Wood Road from the gates and Lodge which are still on Shirecliffe Lane. The 19th Century saw heavily industrialisation of the Upper Don Valley, requiring ganister, charcoal and timber from Parkwood Springs. The fields of the Lords Wood were bought by one of the first Freehold Land Societies for building houses for the ‘40 shilling landowners’. This was an early form of building society where people contributed their 40 shillings for the right to vote as a landowner, and to have the opportunity to build a house on the land. The larger houses built under this scheme were soon accompanied by rows of terraces and back to back houses built for steel and railway workers. This created Parkwood Springs Village, which was finally demolished in clearances of the 1970s. By 1845 the Duke of Norfolk’s Estates had sold land on the lower parts of Old Park Wood for the Manchester, Sheffield and Lincolnshire Railway. Neepsend station was built below the village, which was reached only under a narrow railway bridge (See our History Trail article and Barbara Warsop’s book for details of Parkwood Springs Village). Wardsend cemetery, the cemetery for St.Phillips Church at Neepsend, was developed alongside the River Don also on part of Old Park Wood. By the end of the 19th Century Shirecliffe Hall was occupied by H.E. Watson JP, ‘who worthily upholds the historic character of his mansion.’ Pitsmoor was developing as a suburb of wealthy professionals – doctors, lawyers, mill owners and managers. Therefore rather than Shirecliffe Hall being firmly in command of Parkwood Springs, it was now focused more upon Pitsmoor Village. One of the Watsons, however, found the drive in his carriage too steep coming up Shirecliffe Lane, therefore he had a more gentle route created across Parkwood Springs to Herries Road and into the city from there. During the 18th and 19th centuries life expectancy was short for children and industrial workers (file makers, grinders, cutlery workers, miners). In the late 19th century Pitsmoor Church Parish magazine described the philanthropy of the local gentry – rather than the landowners - who held church ‘teas’ for the poor of the parish. Sir Henry Watson donated gifts of half a pound of tea to the aged poor who attended the ‘teas’. ‘Mr. Watson is the Chairman of the Borough Conservative and Constitutional Association, a Justice of the Peace for the West Riding, a Town Trustee, a Church Burgess, a director of Chas. Cammell and Co. Limited, and to put it shortly one of the most prominent and popular of local gentlemen.’ 20th Century The 20th Century saw the most devastating changes to the Shirecliffe Estate and the grounds of Parkwood Springs reducing it to a blot on the landscape for Sheffield. The 1926 General Strike saw the final trees in the woodland felled completely by impoverished local people for firewood. In the 1930s/40s the area was used as a military base to protect the Don Valley and ammunition stores from enemy aircraft. Disaster struck with the bombing of much of Parkwood Springs Village and Shirecliffe Hall. Both were demolished by the 1970s. The Duke of Rutland sold land for quarrying - and subsequently for the landfill site – for the gas holders and power station with cooling towers alongside the river Don. By the 1950s ownership of much of the upper areas of the original woodland reverted to the City Council. The connection of Shirecliffe Lane with Rutland Road was completed by the 1950s with the building of Cooks Wood Road - through Cooks Wood. The upper part of Shirecliffe Lane was renamed as Shirecliffe Road. Landfill and industrial works reduced the area to a bare hillside with little natural growth. In the 1970s a youth job creation scheme replanted trees and restored footpaths, but the area was mainly deserted and despised by local people for the effects of the landfill site which brought plagues of rats and flies to people’s homes and filled the air with noxious odours and red dust. Nevertheless nature flourished and gradually the area has returned to the area of beauty it once was. 21st Century - From Deer Park to Country Park The restoration has begun to renew the area as a Country Park for local people to enjoy – not just for the nobility – and the deer have returned. The area and boundaries of the original estate are still very similar today. In the past the deer park evolved gradually over the years, but the aim of being productive and a lucrative asset eventually destroyed the area for local people in order to profit the wealthy. We now have the opportunity for Parkwood Springs to be of benefit to people’s health by providing a natural environment instead of damaging health through the effects of industrialisation and poverty. It is now our responsibility to ensure that the Country Park meets the needs of the Community and can be protected to provide a welcoming green space so close to the city centre, conserving wildlife for everyone to enjoy and encouraging people to value and be proud of Our Country Park in the City. Carol Schofield Friends of Parkwood Springs Ivy grows prolifically in shaded areas and in poor soils, be they wet, dry or acidic. Our native common Ivy changes form depending on where it is growing. As ground-cover and when adhering to tree-trunks, walls and other structures the leaves are 3 or 5 lobed on short stems. In this form, Ivy has no flowers or fruits but the dense cover, while capable of crowding out other plants, can provide valuable nesting sites and protection for insects, birds and small mammals, including bats.

Perhaps the most easily recognised of all our native trees the Holly grows in most soils except those that are very wet. The native form, slow growing, can reach a height of 20 metres and live for 300 years. Holly often occurs as a tree in old hedgerows because, in the past, it was considered bad luck to cut it down. There are many decorative forms which are often planted in gardens and parks- they can have the classic prickly leaves or be smooth, have the dark-green glossy leaves of our native trees or be variegated silver or gold.

Another Victorian poet and novelist, George Meredith, (b1828), in “Love in the Valley” referenced this silver-white colouring, especially obvious in young leaves, writing: “Flashing as in gusts, the sudden-lighted whitebeam”.

Richard Mabey, in his wonderful book “Flora Britannica”, thinks that John Evelyn, writing of the Service tree in 1670, may actually have been writing of the Whitebeam which didn’t get this name until the 18th century. Evelyn wrote: “The Service gives the Husbandman an early presage of the approaching spring, by extending his adorned Buds for a peculiar entertainment, and dares peep out in the severest Winters”. The tree was often known as the Service tree in the past. |

|

About us |

Resources |

|